Backyard duck molting: what, when, and why it happens

Tyrant Farms' articles are created by real people with real experience. Our articles are free and supported by readers like you, which is why there are ads on our site. Please consider buying (or gifting) our books about raising ducks and raising geese. Also, when you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more

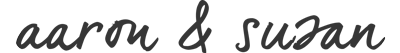

Ducks molt, aka lose their feathers. If you’re a backyard or pet duck parent, here are some things you should know about your molting ducks to make sure they’re staying healthy.

If you’re a new duck parent and you notice: a) piles of duck feathers on the ground, or b) your beautiful, sweet-natured duck suddenly becoming ornery and looking partially plucked, don’t despair!

That pile of feathers doesn’t mean your duck was eaten by a predator (hopefully). And the missing plumage and grumpy attitude doesn’t mean anything is wrong with your duck. Rather, he or she is simply “molting.”

What is molting?

Molting is the process whereby birds lose and replace their feathers. Having good feather quality is important for a bird’s health, survival, mating, and social standing, so replacing old feathers is an essential process.

Types of feathers and their function

Ducks have three types of feathers:

- Flight feathers – These are the large feathers on their wings and tails which allow them to fly.

- Contour feathers – These are the smaller feathers covering their bodies that help make them waterproof and buoyant.

- Down – These are the small, fluffy feathers beneath their contour feathers that keep them warm.

Your duck may molt different types of feathers depending on where they are in the molting cycle.

Two species of domestic ducks, two different molting cycles

Different species of birds (including different species of ducks) may have different molting cycles. There are countless species of wild ducks around the world. The two duck species that have been domesticated are:

- Mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) – Perhaps the most well-known duck species, Mallards are the species that most domesticated ducks originated from. Since we raise Mallard-derived duck breeds, they’re the primary focus of this article. Also, we use our Welsh Harlequins for pictures in this article since they’re sexually dimorphic, e.g. males and females have different feather colorations.

- Muscovy ducks (Cairina moschata) – Another type of wild duck primarily Native to Central and South America which has also been domesticated. They’re in the same family, Anatidae, as Mallards but are a completely different genus and species than Mallards. (If you’re curious, you can find out more about Muscovies vs Mallards in Episode 2 of our Duck Keeper’s Corner vodcast.)

What does this have to do with molting? Wild Mallards have a different molting cycle than wild Muscovies. Muscovies only molt once per year in the fall.

However, wild Mallards go through multiple types of molts each year. They also develop two distinct plumage coloration patterns: nuptial plumage or eclipse plumage. More details:

- Nuptial plumage is characterized by the showy bright green head and curly drake tail feather of the males which develop in late summer-fall as males and females pair up for the following breeding season. This is more of a shift in coloration than a major loss of feathers. Also, female nuptial plumage is much less visually pronounced than males’ plumage.

- Eclipse plumage is characterized by rather drab looking males whose feather colorations are hard to distinguish from females. The boys also lose those cute drake curls. This is the big, messy simultaneous wing molt where they lose all their flight feathers and are completely flightless for up to 45 days. (Despite their wishes, most domestic breeds can’t fly.) With some variation by sex, eclipse plumage develops in late-spring through summer after breeding season and also helps keep the males camouflaged from predators.

- Nest molting is where females pull out some of their down and perhaps even contour feathers to feather their nests to help maintain ideal temperature and humidity for egg incubation. This isn’t a true molt, since they’re pulling their feathers out with their bills. However, we have noticed that when a previously broody momma duck is done raising her young, she’ll experience a hormonal shift that triggers her eclipse molt (replacement of flight feathers).

- Juvenile molt is where young ducklings lose their baby feathers as they develop their first set of true feathers (juvenile feathers) when they’re 6-8 weeks old. They’ll look like awkward teenagers until they sexually mature and molt their juvenile feathers in late summer.

Now, here’s where things can get confusing: the above info pretty well applies to all wild Mallards. However, your domesticated ducks can have a completely different molting schedule than wild ducks or even go more than a year without molting their flight feathers if they’re constantly in egg-production mode.

Pictures to help illustrate molting in backyard ducks:

Why your backyard duck might have a different molting cycle than wild ducks

It’s not easy being a wild Mallard — or any bird for that matter. Taking in enough calories and macronutrients during each seasonal phase is a challenge.

As the Audubon Society says: “Molting is energetically expensive—as is migration and breeding. So, birds make sure these three activities don’t overlap.” And even more energetically expensive than molting is egg laying…

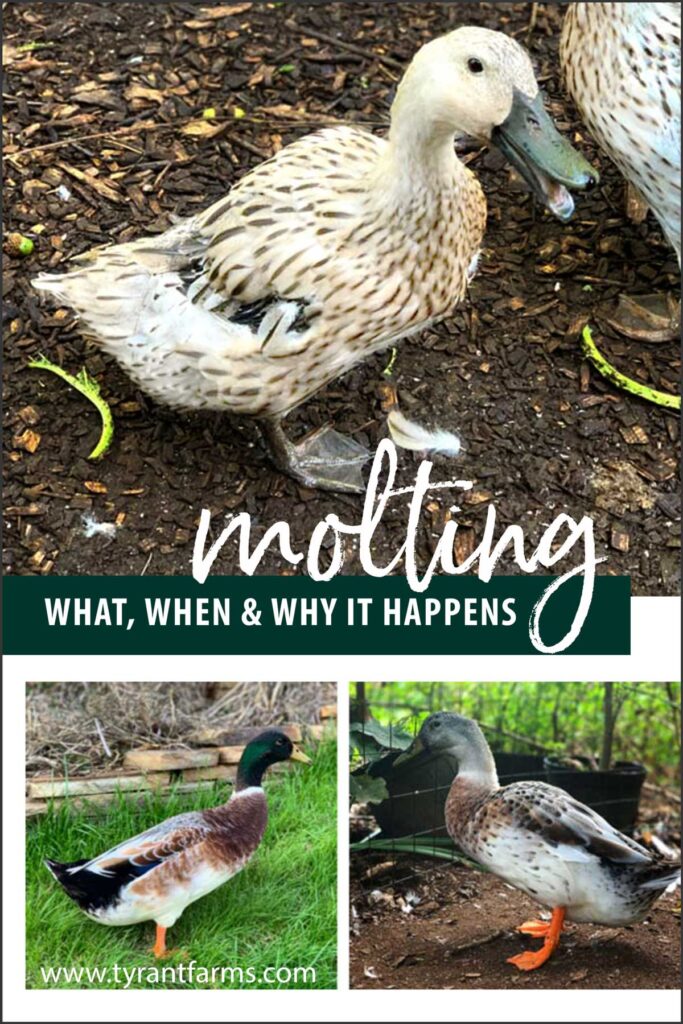

Our spoiled-rotten ducks are pretty far removed from the rigors of being a wild Mallard. They can’t fly. They have humans constantly supplying them with calorie-dense feed and treats. And they have a dry, predator-proof coop to sleep in each night.

However, our girls do lay far more eggs than a wild Mallard. We’ve had ducks lay hundreds of eggs per year versus (at most) 30 eggs per year that might be expected from two broods in a wild female Mallard.

The point being: despite nearly identical genetics to their wild ancestors, domesticated waterfowl live in a completely different environmental context. Therefore, their molting cycles can be quite different too, as we’ve experienced in our flock.

Predicting your domestic ducks’ molting time is like trying to read tea leaves…

In The Ultimate Pet Duck Guidebook, author Kimberly Link says the following about her domesticated ducks molting:

“…not only is every duck different, but males and females are different too. I’ve noticed that for the most part, ducks live their own schedules. Some ducks molt “on time,” while others molt early and still others molt late. Feathers dropping out of some ducks are extremely noticeable, while others seem to experience an almost transparent transformation. When and how your ducks molt often depends upon their breed, gender, genetics, climate, weather, lighting and diet.”

This quote describes our experiences as well, and we’ve been raising different breeds of ducks for well over a decade. Even our ducks that are the same age, breed, sex, live together, eat the same food, and experience the same weather conditions, will often molt at different times for reasons unbeknownst to us.

Also, sometimes one of our ducks will continue laying eggs much longer than we’d prefer (250+ days), which keeps her body from molting and remineralizing. If one of our ducks starts to look too run down — as evidenced by low body weight and poor feather health — we’ll make her go broody, and a molt is soon to follow.

Do ducks need any special treatment while molting?

As you might imagine, emerging feathers seem to be painfully sensitive to ducks. As the larger feathers come in, even your sweetest tamest ducks will likely not want to be handled, so give them their space!

Also, as we’ve already mentioned, it takes a lot of energy and nutrition for a duck to replace their feathers. In the wild, this process is synchronized with the availability of certain high-nutrient (especially protein-rich) foods, e.g. aquatic invertebrates.

Hopefully, your domesticated backyard or pet ducks are already getting excellent nutrition from a waterfowl-specific feed supplemented with fresh greens, treats like mealworms, and whatever they’re able to forage during the day. In this case, no special care is required during a molt — especially if your other ducks are NOT molting.

Providing too much protein in a duck’s diet can be detrimental to their long-term health, causing them to lay too long or even leading to organ damage.

Our goal is to raise the healthiest possible, long-lived ducks, NOT produce the most eggs possible each year (or produce meat). However, people raise ducks for different reasons, and that’s fine too.

For instance, in Storey’s Guide to Raising Ducks, Dave Holderread suggests the following:

“Growing feathers require additional protein (15 to 16 percent high-quality protein is usually adequate) and other nutrients; therefore, a well-balanced diet during a molt will encourage healthy plumage. The addition of animal protein (5-10 percent by volume cat kibbles is a good source) and 10 to 20 percent oats (by volume) during the molt can produce wonderful feather quality.”

Our concern with this recommendation would be that a duck would not eat the oats and kibble in the proper ratios, thereby causing a nutrient deficiency.

Another way to give your ducks a protein boost during the ~1 month window when they’re molting is to give them extra mealworms, worms, crickets, soldier fly larvae, minnows, etc. Just don’t overdo it!

Geeky final note: Humphrey-Parkes molt cycle terminology

Just to fend off potential criticism of the info we’ve provided in this article: we know that scientists have actually taken a deep-dive into the topic of duck molting, therein developing a standardized nomenclature called the Humphrey-Parkes system, which defines stages in ducks’ molt cycles as prebasic, prealternate, or presupplemental.

However, we think this terminology can get a bit confusing for people who are just trying to figure out what the heck is going on with their molting pet and backyard ducks, so we’re trying to keep things a little simpler here!

Molt on!

We hope the information in this article has helped allay any concerns you might have about why your duck is suddenly losing feathers. We also hope you have much more appreciation for the complexity and uniqueness of your wonderful waterfowl!

Get quacking with more duck articles from Tyrant Farms:

- What to feed pet or backyard ducks to maximize their health and longevity

- How to build a DIY backyard duck pond with self-cleaning biofilter

- Why and how to make your duck go broody

- Why and how to raise mealworms (especially if you’re a duck parent)

- 17 tips to keep your ducks safe from predators

- Can birds change sex? The curious tale of Mary/Marty the duck…

…and dozens of other helpful backyard (and front yard) duck articles.

Connect with us on Instagram:

Have you ever noticed your ducks quack change during a molt? My 1.5 year old female welsh harlequin recently dropped all her flight feathers and has sounded quite different (and is definitely a little moodier). She is sounding a little “honkier” these days

Hi Marion! I can’t say we’ve ever observed a notable *qualitative* difference in our ducks’ vocalizations when they’re molting. Instinctively, they do tend to get a bit more quiet (a quantitative difference) during molts where they lose their flight feathers, since being flightless would make wild ducks especially prone to predation. They can definitely get grumpier and moodier during molts, as you also noted. We have had ducks’ voices temporarily change for unknown reasons, but that’s never precipitated any sort of serious medical event. (Knock on wood.)

When a duck is molting, do they scratch themselves constantly? How do I know if molt or mite? The pair I have are about 9-10 weeks old

Hi Teresa! You might be interested to read the earlier comment on this article from Melissa Nannen where she said: “we are experiencing the molt right now and I initially was very perturbed when all of the front feathers of two of my ducks started dropping. They are 10 and 9 weeks old, and I didn’t realize they would molt so quickly after getting their adult feathers.”

Yes, when your ducks molt they’ll do a lot of extra preening and scratching. It’s actually quite unusual for ducks to get mites if they have access to clean swimming water. Just to be sure, you may want to take a close look at the feathers and see if you see any tiny mites. They’re typically red, black, or brown in color and are visible (albeit very tiny) to the naked eye.

Thank you – we are experiencing the molt right now and I initially was very perturbed when all of the front feathers of two of my ducks started dropping. They are 10 and 9 weeks old, and I didn’t realize they would molt so quickly after getting their adult feathers. I was also concerned I wasn’t feeding them the proper protein ratios – I normally would have cut their 16% protein down to the 13% or so you recommended in your feeding article, but when I saw them dropping feathers I kept it at 16%. A well timed article – thank you! By the way, did you ever notice a pecking order shift during the molting period? Our one duck who has always been in charge all of sudden seemed to drop in rank among the other ducks, and the smallest and youngest seemed to rise a few notches above her. She is otherwise acting as she was, but she isn’t nearly as bossy. I didn’t know if it was temporary because of the molt or the youngest one was coming into her own, so to speak. It’s kinda of interesting to see the dynamic shift because I don’t think they’ve figured out who is in charge – it’s just obvious that my poor dopey Pekin is definitely on the bottom of the order. Ducks are such fascinating creatures – truly I am indebted to you and your articles for introducing such wonderful animals into our lives. 🙂

Ha! Funny to hear this. Yes, when our ducks molt it seems to throw flock dynamics a bit out of whack temporarily. Not sure the exact reason, but our guess is it’s due to hormonal shifts that correspond with the molt. Even at baseline, our girls get along well and don’t seem to have too strict of a pecking order. However, we (and our drake) have noticed that there is a more dominant younger one, Pippa, who our drake favors. There’s also another maternal elder flock co-leader (Jackson, our oldest). The others all generally fall in line behind those two, and Jackson even has a guard duck, Marigold, that follows her everywhere and loudly warns of any potential danger. When they’re molting, social dynamics go into disarray, but they do seem to return to normal once they’ve feathered back in. Years ago, we had a duck named Svetlana who was the flock diva/queen, and she’d even beat up on Marigold from time to time. But during a molt, we saw Marigold bully Svetlana. Ducks are indeed fascinating creatures and an endless supply of entertainment. Glad to hear you’re enjoying your feathered family members. 🙂

Great article!

Thank you!