Usnea Lichen (Usnea spp.): How to Find, Identify, Harvest, and Use Old Man’s Beard

Tyrant Farms' articles are created by real people with real experience. Our articles are free and supported by readers like you, which is why there are ads on our site. Please consider buying (or gifting) our books about raising ducks and raising geese. Also, when you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more

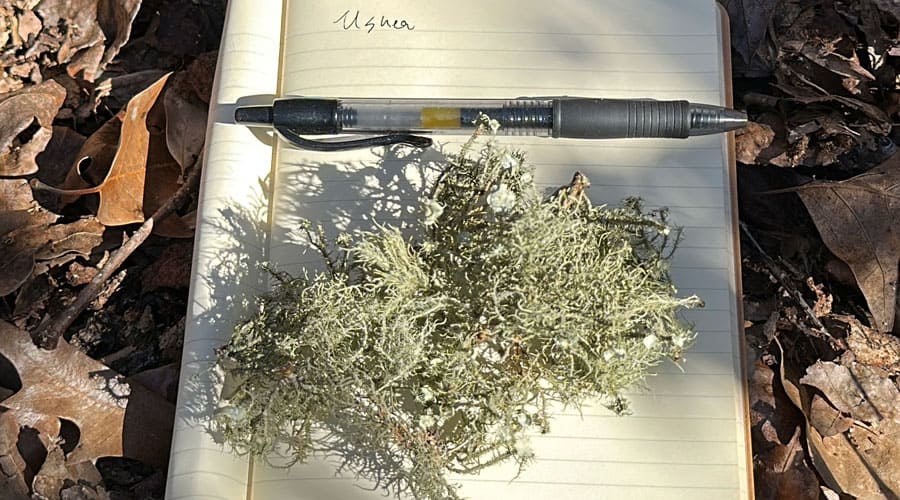

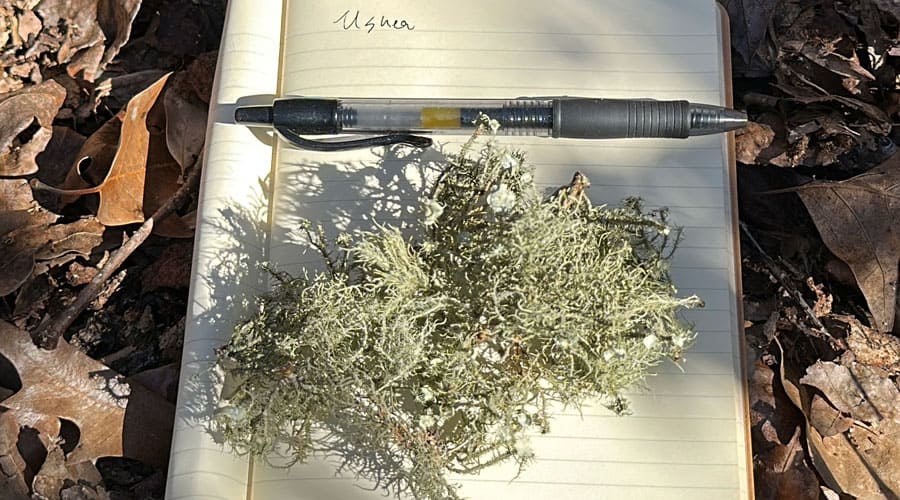

This article is a supplemental guide to our video about foraging usnea lichen on our YouTube channel, Untamed Eats. (Video link coming soon!) | Download 1-sheet usnea Quick Guide

Why Lichen Is One of the Most Amazing Life Forms on Earth

Before we dive into usnea lichen specifically, it’s important to understand what lichen actually is — and why it matters.

Lichen Is Not a Single Organism

Lichen is not an individual species. It is a holobiont — a symbiotic partnership between:

- a fungus (the mycobiont) that provides structure and protection;

- either green algae or cyanobacteria (the photosynthetic partner, aka photobiont) that produces carbohydrates; and

- (sometimes) bacterial partners and additional species of fungi.

In 1867, the Swiss botanist Simon Schwendener was the first to propose that lichens were composite organisms rather than single species. His hypothesis was largely disregarded at the time, but was eventually proven true. 10 years later in 1877, German mycologist Albert Frank is credited with coining the term “symbiosis,” based on his study of lichens. This was a revolutionary concept at the time.

Likewise today, despite initial skepticism, the concept of the holobiont is now becoming widely accepted in biology thanks to pioneering work by scientists like Lynn Margulis. Simply put, a holobiont is an organism plus its associated microbial partners functioning together as a unit.

In that sense, lichens are not strange or unusual — they are simply an especially visible example of how life works.

A few other examples:

- Every complex cell in an animal’s body contains mitochondria — descendants of ancient bacteria that merged with early eukaryotic cells over a billion years ago.

- Plants rely on fungal mycorrhizae and other microbes below the soil surface.

- Corals are colonies of tiny animals which rely on algae.

- Humans rely on trillions of microbes in and on us, which collectively form our microbiome.

Upon deeper inspection, what we call an “individual” is often a community.

Three primary forms of lichen

As you start to notice the lichen all around you, you might also want to note the three primary growth forms to help with identification:

1. Crustose – Crustose lichens have a crusty growth form.

2. Foliose – Foliose lichens have a leaf-like growth form.

3. Fruticose – Fruticose lichens have a shrubby and hair-like growth form. Usnea is a type of fruticose lichen.

Lichen Love: Amazing Lichen Facts You Should Know

1. Lichens are one of the most successful life forms on earth

Fossil evidence suggests lichens have existed for at least 410 million years. Today, there are tens of thousands of lichen species worldwide, and they can grow nearly anywhere: deserts, tropical forests, arctic tundra, and even inside rock (endolithic lichens).

2. Lichens can live to be thousands of years old, but they tend to be incredibly slow-growing.

A map lichen growing in northern Alaska is the oldest known lichen alive today, and may be over 10,000 years old! Despite their longevity, lichens are very slow growing. Some lichens grow only 1 mm per year.

This combination of unique features (old age + slow predictable growth rate) allows scientists to use lichens for archaeological dating, aka lichenometry. For instance, lichenometry was used to help figure out the age of the large stone Moia face statues on Easter Island.

3. Lichens help make life on land possible.

Over 400 million years ago, pioneering lichens began moving from ocean tidal zones to inland habitats, helping form the world’s first soils by chemically weathering rock and trapping organic matter. While it currently appears that plants got to land first, future findings may shift those dates.

Today, lichen continues to play a critical role in ecosystems around the world, building soil and cycling carbon, nitrogen, and other nutrients.

4. Lichen is a living air quality monitor.

Lichens are highly sensitive to air pollution because they absorb water and nutrients directly from the atmosphere — making them reliable bioindicators of air quality.

Usnea — the genus of lichen which is the focus of this article — is particularly sensitive to air pollution, which is why you tend to only find it growing on trees inside forests with high air quality.

What Is Usnea Lichen?

Usnea is a genus of fruticose (shrubby, hair-like) lichens commonly called “old man’s beard,” although not all usnea lichen resembles an old man’s beard.

There are over 100 described species of usnea worldwide, and they are found primarily in forests with good air quality. They occur on every continent except Antarctica and grow on tree bark, fallen branches, and occasionally other substrates.

Usnea’s identifying features

Here are characteristics and features that can help you identify usnea lichens:

- grow year round and almost exclusively on trees

- typically pale green to gray-green in color

- fruticose (hair-like or shrubby growth pattern)

- cross-section of branches are round, not flat

- only grows when air quality is good

- attached to the bark of a tree at a single holdfast point

A Unique Structural Feature to Identify Usnea

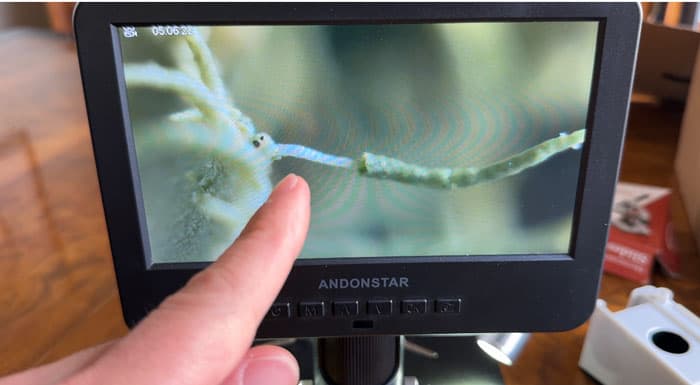

All usnea species share one defining characteristic that helps differentiate them from other lichens: they have an elastic white central cord running through the thallus (body) and branches.

When an usnea branch is gently pulled apart, a stretchy internal filament is visible. This cord is composed of tightly bundled fungal hyphae. Note that this feature may be harder to detect when usnea is dried out and brittle. The internal cord is much easier to detect when usnea is damp/wet.

This internal cord is the easiest and most reliable field identification feature for lichen species in the Usnea genus. If a lichen you’re trying to ID does not have the internal white cord, it is NOT usnea.

Species-Level Identification (Advanced)

Many lichens (including usnea) are so similar in appearance that even experienced lichenologists rely on laboratory techniques for definitive identification. This is true of two usnea species growing where we live in Upstate South Carolina: Usnea strigosa and Usnea endochrysea.

Identifying the exact species often requires some combination of:

- Microscopic spore measurement

- Chemical spot tests

- Thin-layer chromatography (TLC)

Fortunately, for practical use, all Usnea species can be used interchangeably and can be distinguished from other lichens by the internal white cord.

Warnings and Poisonous Lookalikes

Depending on where you live, there may be toxic usnea lookalikes to be aware of. In North America, two toxic usnea lookalikes are:

These species are:

- bright yellow (not pale green)

- primarily found in western North America, not in the east

- lacking the elastic white internal cord characteristic of usnea

How to Sustainably Harvest Usnea

Because lichens grow extremely slowly and are important members of their ecosystems, sustainable harvesting is critical.

We recommend:

- Never harvest usnea from living trees unless there is a true emergency.

- Only collect from fallen branches or downed trees. (After a heavy storm is an ideal opportunity to forage.)

- Harvest sparingly — take only what you need.

Ethical foraging protects ecosystems and supports future foragers (including future you!).

How Does Usnea Reproduce? (Using Usnea strigosa as an example)

If you’re like us, you might be curious to know how a multi-species holobiont like usnea lichen reproduces. Their reproduction is more complex than that of a typical plant or fungus.

Most usnea reproduction occurs asexually. Small fragments of the lichen break off due to wind, animals, or branch fall. If those fragments land in a suitable location with adequate moisture and light, they can continue growing.

This method is efficient because it preserves the full partnership — fungal component plus photobiont — intact.

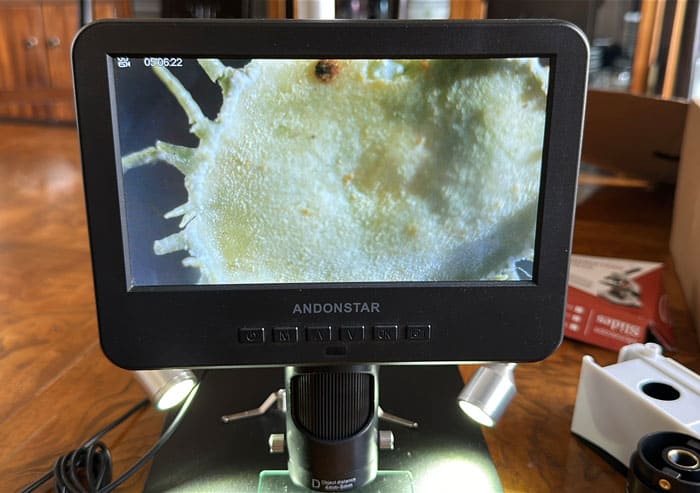

Lichen can also reproduce sexually. In species such as Usnea strigosa, sexual reproduction occurs through structures called apothecia — disc-shaped reproductive organs produced by the fungal partner (phylum Ascomycota).

Apothecia release fungal spores into the environment. However, those spores do not contain the algal partner. For a new lichen to form, the fungal spore must:

- Land in a suitable habitat.

- Encounter a compatible algal partner in the division Chlorophyta.

- Successfully re-establish symbiosis.

Note that apothecia are not always present on Usnea strigosa, so their absence does not rule out identification.

Is Usnea a Food?

Unlike some lichens (e.g. Islandic lichen, Cetraria islandica), usnea has not historically been used as a food source in a conventional sense.

We recommend thinking of usnea primarily as a medicinal or functional lichen rather than a primary food source.

Usnea is composed of about 50 percent water-soluble polysaccharides (complex carbohydrates) produced by the fungi, anywhere from 0.2-6% usnic acid produced by the algae, and a laundry list of other secondary metabolites.

We use usnea in small amounts and in short duration, not in high doses or on a daily basis. That’s because usnic acid can cause liver damage if used in high doses or long durations. Like many medicines, the dosage makes the difference between harm and benefit.

Our favorite use of usnea is to make a simple tea, which smells and tastes wonderful (especially with a small bit of stevia added). Simply add a small handful of usnea per 2 cups of water and keep it covered at a low boil for about 30-45 minutes.

We describe usnea tea as grassy, woodsy, and floral all at once. Since usnic acid is not water soluble, very little is extracted from the algae when making tea.

We also like to add small amounts of usnea to ferments like sauerkraut. (Quantity is roughly a handful of usnea per quart jar.) Since the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in sauerkraut do naturally produce a small amount of ethanol alcohol biproduct during the fermentation process, we presume that at least some of the usnic acid (which is alcohol-soluble) is extracted over the ~30 day fermentation window.

Another good use of usnea: If you happen to get a bad cut while out hiking, usnea can be chewed up and applied as an emergency wound care poultice. That’s because usnea has potent antimicrobial and wound healing properties.

What does the research literature say about usnea’s medicinal potential?

Here are some excerpts from a 2021 meta review of available studies on the medicinal qualities of usnea published in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology:

- “The broad scientific studies on this lichen have proved its multidirectional biological effect, such as antimicrobial activity, which is attributed to its usnic acid content.”

- “Analysis of the scientific literature regarding traditional uses and bioactivity research showed that Usnea sp. extracts exhibit high antibacterial activity. The Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and aquatic oomycetous fungi were the most sensitive…”

- “The results show that the use of Usnea sp. in traditional medicine can be scientifically documented. Studies show that usnic acid is the active compound present in Usnea sp. extracts. Usnea sp. extracts contain compounds other than usnic acid as well with biological effects.”

- This review also has an interesting note about the potential harmful effects of usnic acid on the liver, and illustrates how, like many medicines, the dosage is what makes the difference between a medicine and a poison: “The compound administered to patients at a dose of 3 mg daily caused liver pain. With reducing its dosage to 1 mg per day, the symptoms were removed.”

What about usnea’s wound healing potential? A 2025 study on lab mice showed usnea extract significantly improved both wound closure time and increased collagen density at the injury site during healing.

All that said, if you have compromised liver function, you may want to avoid usnea altogether or consult a qualified healthcare professional before use.

We hope this information helps you better appreciate lichen: a fascinating holobiont that’s critically important to terrestrial life and a potential source of diverse range of human medicines.

-Aaron and Susan