Tradescantia virginiana – a native edible plant common in home landscapes

Tyrant Farms' articles are created by real people with real experience. Our articles are free and supported by readers like you, which is why there are ads on our site. Please consider buying (or gifting) our books about raising ducks and raising geese. Also, when you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more

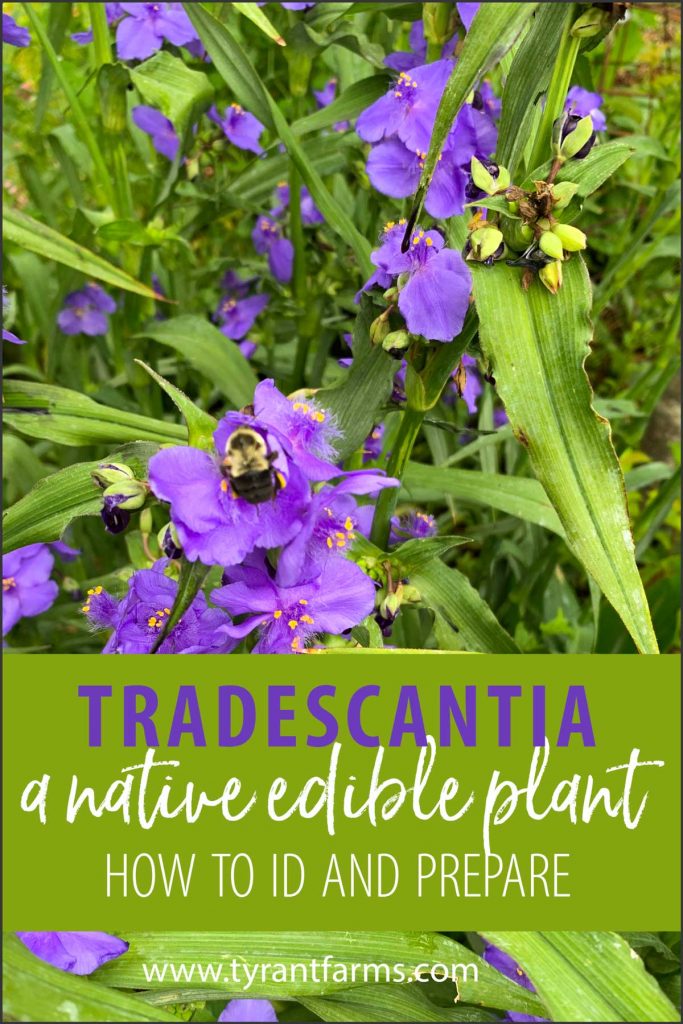

In our Zone 7b garden, there’s a gorgeous, purple-flowering plant that’s covered with pollinators from May – July: Tradescantia virginiana. This plant is fairly common in flower gardens due to its showy blooms, but we feel it deserves a closer look due to its edibility as well…

Tradescantia virginiana: a brief history

The genus Tradescantia is home to at least 75 distinct plant species that are also commonly called “spiderwort“. Some species of spiderwort are edible, some are not. Regardless, if you ask us, “tradescantia” is a much more attractive name than spiderwort, especially when trying to entice someone to eat it.

The genus is so-named in honor of John Tradescant the Younger, a naturalist and explorer who came to Virginia in the 1600s. Tradescantia virginiana was one of the plants that caught his eye and returned with him to England where it soon became popular in gardens.

John Tradescant certainly didn’t discover this showy plant, however. According to the USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), Tradescantia virginiana has an interesting ethnobotanical history:

“The Cherokee and other Native American tribes used Virginia spiderwort for various food and medicinal purposes. The young leaves were eaten as salad greens or were mixed with other greens and then either fried or boiled until tender. The plant was mashed and rubbed onto insect bites to relieve pain and itching. A paste, made from the mashed roots, was used as a poultice to treat cancer. A tea made from the plant was used as a laxative and to treat stomachaches associated with overeating. Virginia spiderwort was one of the seven ingredients in a tea used to treat “female ailments or rupture.” It was also combined with several other ingredients in a medicine for kidney trouble.”

We have more to say about eating Tradescantia virginiana below.

Tradescantia virginiana: a great plant for brown thumbs

The native range of Tradescantia virginiana is the entire east coast of the United States, from Maine south to Florida and westward to the Mississippi River. Even if you don’t grow it, be on the lookout for tradescantia when you’re out on hikes — the small, showy purple flowers are perhaps the easiest way to quickly ID the plant.

If you consider yourself a “brown thumb” (e.g. someone who hasn’t gardened enough to graduate to a green thumb) this is a plant for you. Here’s why:

- Tradescantia grows from Zones 4-9, so hot summers or cold winters won’t kill it.

- It tolerates wet conditions or droughts equally well and can grow in virtually any soil type as well.

- It’s a perennial so it will come back year after year regardless of your neglect.

- It grows in full sun or part shade.

A tradescantia growing tip: put a sturdy 3-4′ tall plant cage around your tradescantia to keep the plant more ruly as it grows. The tall thin outer stalks tend to flop over late in the season, rooting where they touch the ground.

Tradescantia virginiana dies back to the ground during the cold months and bursts back to life in late winter-early spring. From there it send up clusters of long stems that max out at 3-4′ tall. At the end of each stem, clusters of showy purple flowers form.

Each individual tradescantia flower only lasts about a day, but is soon replaced the following day by new flowers. In the morning when the nectaries are full, our plants buzz with the sound of happy bees (both natives and honeybees).

Butterflies seem quite fond of the flowers as well.

How to eat Tradescantia virginiana

Over the years, we’ve read lots of accounts from market farmers and home gardeners alike about the edible attributes of Tradescantia virginiana. Some people sing its praises, others say it’s more of a famine food.

In our opinion, the culinary potential of tradescantia is all about which parts of the plant you use. Perhaps more importantly, when you harvest them is equally important.

In short, tradescantia requires a more intimate relationship and understanding than you might have with a beet, which you simply pull out of the ground once the root reaches a certain size.

Edible parts of Tradescantia virginiana

Every part of Tradescantia virginiana is edible. (We make no such claim about other species in the Tradescantia genus.)

Here’s our quick culinary assessment of each part of the plant plus when & how they’re best to consume:

1. Tradescantia flowers

Tradescantia virginiana blooms from late spring – early summer. Our flowers are purple, but other cultivars or sub-species can produce flowers which range in color from light violet to white.

Each flower is short-lived, only lasting for about a day. The flowers are best picked in the morning and immediately stored in the fridge. Even then, their shelf-life is quite short, so you’ll want to use them by dinnertime.

Tradescantia flowers are fairly bland in flavor, especially relative to various other edible flowers you can commonly find. Their best use: an attractive garnish. Or perhaps an even better use: leave the flowers for your honeybees and eat them in honey form.

One small warning: tradescantia flowers will turn anything they touch dark purple, including your fingers or cutting boards.

2. Tradescantia flower buds/clusters

Flower clusters form at various points along tradescantia’s stalks. In our opinion, the unopened flower buds are the tastiest part of the plant with the best texture.

It doesn’t take much work to gather a nice pile of tradescantia flower buds given how prolific they are. They also easily snap off the stalks so you don’t even have to cut the stalks to remove the buds if you don’t want to.

Tradescantia flower buds/clusters are quite good sauteed like rapini: a little olive oil, sea salt, and diced garlic is all that’s needed. They have a pleasant floral flavor that is improved by cooking.

Same warning as with open tradescantia flowers: the buds will stain hands and cutting boards! Pure speculation, but perhaps this feature is why one of tradescantia’s older common names was “Indian paint.”

3. Tradescantia leaves

Tradescantia leaves are best eaten when tender and young in late winter through early spring. They have a pleasant mild taste, kind of like a grassy spinach. As the plant ages, tradescantia leaves get tougher and more fibrous.

Like the flowers, tradescantia leaves are somewhat ephemeral. Get them washed and in the fridge asap and use them within 1-2 days.

The older tougher leaves are perfectly fine to eat too. In fact, they’re a nice green to have around in our scorching hot summers when all the standard garden greens (lettuce, kale, spinach, etc) have long since died out. However, they’re best chopped small and cooked into dishes (quiche, stews, etc), rather than eaten raw.

4. Tradescantia stalks/stems

Tradescantia stalks are often described as “tasting like asparagus.” While we like them, we much prefer asparagus.

Don’t let that critique dissuade you from eating tradescantia stalks, however, because they are quite good. When you harvest them, you’ll notice that they have a mucilaginous sap, similar to okra or Malabar spinach. This seems to go away when they’re cooked.

The outer sheathing on larger, more mature stalk bases can be quite fibrous, like the base of an asparagus spear picked too late. It’s best to harvest higher up on the stalk and from younger stalks, which you can do throughout the spring and summer.

In our opinion, perhaps the best use of tradescantia stalks in the kitchen would be to slice them into small bite-sized pieces then use them in stews, jambalayas, and other African-inspired dishes as a substitute for okra or right alongside it.

Update: Bill Bennett, a reader, wrote us to also suggest the following use for tradescantia stalks: “The stalks are pretty good lacto fermented (pickled) with the wild garlic garlic from my yard and salt.”

5. Tradescantia roots

As mentioned earlier, Native Americans used tradescantia roots in poultice form as a cancer treatment. The roots are technically edible, but we’ve never dug and eaten ours. (We’ll update this article when we do — or you can leave us a comment below to let us know if you’ve eaten tradescantia roots.)

For now, we’re content with the above-ground edible portions of our tradescantia plants!

We hope the information in this article helps you gain a better appreciation for Tradescantia virginiana: a common native plant you may have growing in your garden or see out on a walk in nature. Now you know how to use tradescantia in your kitchen as well.

Enjoy!

KIGI,

I have had tradescantia virginiana on all my property over several decades, and they are indeed pretty when in bloom and virtually grow themselves. I never once considered, however, that they might also be edible! With an abundance of plants, I will definitely explore some of the culinary possibilities you discuss. I would add one point to your discussion; the best way to get tradescantia to bloom more than once is to cut the plant back to the ground once it blooms in late spring to early summer (where we are in South Carolina). It will then send up new growth for late summer-fall blooming. I look forward to reading more of your delightfully written and informative articles. Oh, the photos are great too.

Thanks for your kind words, and we’re glad to introduce you to a new edible plant! Cutting Tradescantia virginiana back in late spring/early summer to stimulate rebloom is a great tip. One thing we’ve found when trimming ours is that the cuttings easily root, so you can end up accidentally creating new tradescantia patches in spots you might now want them growing. So keep that in mind when cutting!

We are just beginning our urban homestead adventure and have a lot of this volunteering in our space. This article has given me a lot more (much-needed) appreciation for the opportunistic Tradescantia Virginiana! I came to this article from a link on your Stridolo page (the most informative on the topic that I have found thus far). Thank you so much for your outstanding blog!

Thanks so much, Michelle! Glad the information shared has been helpful for you. Best of luck in your urban homestead adventures!

We are just beginning our urban homestead adventure and have a lot of this volunteering in our space. This article has given me a lot more (much-needed) appreciation for the opportunistic Tradescantia Virginiana! I came to this article from a link on your Stridolo page (the most informative on the topic that I have found thus far). Thank you so much for your outstanding blog!

Thanks so much, Michelle! Glad the information shared has been helpful for you. Best of luck in your urban homestead adventures!

We are just beginning our urban homestead adventure and have a lot of this volunteering in our space. This article has given me a lot more (much-needed) appreciation for the opportunistic Tradescantia Virginiana! I came to this article from a link on your Stridolo page (the most informative on the topic that I have found thus far). Thank you so much for your outstanding blog!

Thanks so much, Michelle! Glad the information shared has been helpful for you. Best of luck in your urban homestead adventures!

We are just beginning our urban homestead adventure and have a lot of this volunteering in our space. This article has given me a lot more (much-needed) appreciation for the opportunistic Tradescantia Virginiana! I came to this article from a link on your Stridolo page (the most informative on the topic that I have found thus far). Thank you so much for your outstanding blog!

Thanks so much, Michelle! Glad the information shared has been helpful for you. Best of luck in your urban homestead adventures!

Another for the flowers! Remove the reproductive parts in the middle (alternatively pluck the petals however doing so is more likey to bruise them which results in a less desirable end product), then dry the petals (a day on a windowsill can be all thats needed for these thin thin thinnnnnn petals), store as is once dried from here or move onto these next steps immediately, then grind or crumble the petals into a fine powder. Guess what, we’ve just gone on a journey together creating plant-based and natural purple food dye! Mix the powder into icecreams, puddings, frostings, the likes. I would keep this one to using with things that do not get cooked but just combined. For example, adding the powder to a cake batter would result in a more gray-tinged cake after baking rather than purple, the heat seems to destroy the pigments. Cheers!

Good tip, thanks Logan!

I just broiled some like asparagus with olive oil, salt and pepper. The leaves crisp like broiled cabbage and the pods are really good too. I’m going to try again by starting with the stalks, then adding leaves, followed by the leaves. Its all really quiet good.

I have lots of Tradescantia and love it as an ornamental. My mother grew it and as a child I used to love to squish the purple flowers and think it would make a great ink or dye, if only I could figure it out. It was fun reading your article about the many ways to eat it.

Tradescantia virginiana is a really beautiful plant. It would be interesting to try to make an ink with the flowers – maybe you could paint with it? 🙂 It seems like the purple color oxidizes relatively quickly and turns brown but adding some acid might help arrest that process.