Is pawpaw fruit killing you? Risks of eating Asimina triloba fruit…

Tyrant Farms' articles are created by real people with real experience. Our articles are free and supported by readers like you, which is why there are ads on our site. Please consider buying (or gifting) our books about raising ducks and raising geese. Also, when you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more

Let me start by saying this is a rather heartbreaking article to write… My wife and I ate our first pawpaw (Asimina triloba) fruits back in 2010 and immediately fell in love with them.

The largest native fruit in North America? A delicious mango-banana flavor? A host plant for Zebra Swallowtail butterflies and other pollinators? The virtues of pawpaws are many.

Thus, we planted about ten pawpaw saplings around our property and also zeroed in on prime pawpaw foraging spots in our area as we waited for our trees to mature. From then on, we looked forward to eating raw pawpaw fruit each summer, and never imagined that this beloved fruit might come with some hidden dangers…

GI distress from cooked pawpaw

Then, a few years back when we had family in town, we made a cooked pawpaw dish that gave two family members GI distress. Both these family members are quite robust and had zero prior problems eating raw pawpaw fruit.

Thus, I immediately took a dive into online resources and research literature on pawpaws, and was quite shocked by what I found. First, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, cooking or dehydrating pawpaw fruit seems to significantly elevate the risks of acute negative reactions such as splitting headaches, nausea, severe GI distress, vomiting, etc. (Definition: “Acute” means a condition that onsets suddenly but doesn’t last very long.)

To be clear, as of now, there is no published research literature shedding light on the possible cause(s) of acute negative reactions of ingesting pawpaw fruit. (I’ll add my own suspicions later in the article after providing additional context.) However, there are countless anecdotal cases of people having acute negative reactions to eating pawpaw fruit in various forms, from raw to cooked to dehydrated. In fact, such reactions are so well known anecdotally that we found a pawpaw association newsletter in Ohio warning pawpaw growers never to dehydrate their fruit for commercial use.

However, there is published research on the chronic effects of eating pawpaws and related fruit. (Definition: “Chronic” conditions develop slowly but can last a long time, potentially for the remainder of your life.)

Annonaceae plant family risks

Pawpaws are part of the Annonaceae plant family. Most edible fruits in this plant family live in the tropics. Examples: custard apples and soursops. Pawpaws are a rare exception, since they live as far north as Canada.

Plants in the Annonaceae family contain varying concentrations of annonacin and squamocin, which are annonaceous acetogenins. Annonaceous acetogenins are known to be neurotoxic. Specifically, they appear to kill nigrostriatal cells in your brain. And with repeat exposure (such as regular consumption of pawpaw fruit), the chronic health effects are lumped under the umbrella term “atypical Parkinsonism.”

What’s the difference between Parkinson’s Disease and atypical Parkinsonism? Parkinson’s Disease typically involves a tremor and patients respond well to the medication L-Dopa. However, atypical forms often progress faster, show poor or no response to medication, and feature early-onset cognitive issues or balance problems. Translation: You really, really don’t want to get atypical Parkinsonism if you can avoid it.

(Quick side note: When I was a kid, I watched my grandfather waste away and die from Alzheimer’s disease, another neurodegenerative disease similar to Parkinson’s. If there’s anything I can do to help myself and others avoid such a terrible death, I will gladly do it.)

Pawpaws aren’t a commonly or regularly eaten fruit in the US, so epidemiological risk patterns are hard to detect here. However, in the tropics, fruits such as soursops, custard apples, and their commercial products are commonly consumed, sometimes on a daily basis. There, the risks of Annonaceae plant/fruit consumption are becoming increasingly well documented.

For instance, as far back as 2008, a study published in the journal Movement Disorders, found the following:

Epidemiological data suggested a close association of the disease [atypical Parkinsonism] with the regular consumption of soursop, a tropical annonaceous plant. Experimental studies performed in midbrain cell cultures identified annonacin, a selective mitochondrial complex I inhibitor contained in the fruit and leaves of soursop, as a probable etiological factor. Consistent with this view, chronic administration of annonacin to rats through Alzet osmotic minipumps showed that annonacin was able to reproduce the brain lesions characteristic of the human disease.

Translation: On the Caribbean island of Guadalupe, people who regularly eat soursops (a pawpaw relative) had much higher rates of atypical Parkinsonism. Suspecting the disease was due to annonacin consumption, the researchers then tested their hypothesis by giving annonacin to lab rats, which then presented with the type of brain lesions that would cause atypical Parkinsonism. Yikes!

The dose makes the poison

The adage “the dose makes the poison” is something to consider here. How much annonaceous acetogenins would a person have to consume to put themselves at risk? Over what time period? And what are the concentrations of these compounds in pawpaw fruit vs other Annonaceae fruit?

Depending on the plant species and the type of tissue (roots, bark, leaves, fruit pulp, fruit skin, seeds) concentrations of these compounds may vary.

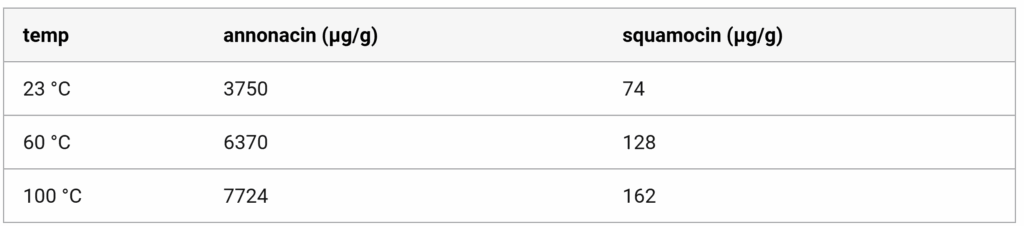

A 2015 study found between 3,750 – 7,724 (μg/g micrograms/gram) of annonacins in pawpaw fruit pulp, with variations depending on the temperature used during the extraction process. The higher the extraction temperature, the higher the detectable levels of annonacin. As best we can tell, this means pawpaw fruit is far higher in annonacin content than other popular Annonacea fruits.

However, since there isn’t a single study that compares levels of annonaceous acetogenins from different Annonacea fruit species using the same extraction process/method, it’s difficult to say for sure. Hopefully, such research will be done in the near future.

Why might cooking or dehydrating pawpaw fruit increase the risk of severe GI distress?

Ok, now that we have context for the causes of the chronic health risks of eating pawpaw fruit, let’s go back to the original question of what might cause the acute response many people experience from pawpaw consumption, especially as the fruit is processed via heating and dehydrating…

This is speculation, aka a hypothesis in need of empirical data, but here’s my guess: annonaceous acetogenins are potent inhibitors of mitochondrial complex I, a key enzyme in the electron transport chain. By disrupting cellular energy production, they can also be toxic to normal cells, including those in the digestive system. Thus, consumption of pawpaw fruit may also trigger gastrointestinal distress, including headaches, nausea, and vomiting.

Since different people have different physiologies (genetics, GI flora, etc), perhaps some people are also going to be much more sensitive to annonaceous acetogenins than others. Whether that susceptibility elevates an individual’s chronic exposure risks is also an interesting question that we hope some intrepid scientists out there will research.

Why does heating or dehydrating the fruit elevate the risks? The 2015 study Determination of Neurotoxic Acetogenins in Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) Fruit by LC-HRMS may shed light on the answer. The study found that the higher the temperature they subjected pawpaw fruit pulp to, the higher the levels of annonacin and squamocin they detected.

Below, I’ve included Table 1, from their study, labeled “Concentrations (in μg/g) of Annonacin and Squamocin Found at Three Different Extraction Temperatures in Lyophilized Whole Pawpaw Fruits from Missouri“:

As you can see in the above table, detectable annonacin and squamocin levels more than doubled in pawpaw fruit tested at room temperature versus pawpaw fruit subjected to boiling temperatures.

I’ve reached out to the study’s corresponding author, Robert E. Smith at the FDA, to get his thoughts on this topic, but have yet to hear back. I’ll update this article if/when he responds.

Do we still eat pawpaw fruit?

As of now, we still eat a few raw pawpaw fruits each year when they’re in season. We’ll never eat it cooked or dehydrated. And we only give a spoonful of it to our young son if he asks for it.

We no longer eat pounds of ripe pawpaw fruit when it’s in season, freeze it for consumption year round, etc. As much as we love the taste of pawpaws, we love having healthy functioning brains and bodies more – and we want them to stay that way for as long as possible.

We’ve also removed most of the pawpaw trees on our property to make room for other food-producing perennials that don’t present a risk to our health. For now, we’ve left the pawpaw trees on the back of our property near our forest since they’re a native plant that benefits lots of other species, even if they’re not great for the humans currently living here.

We’ll also be updating our pawpaw recipe articles with warnings about the fruit so that people can make an informed decision about whether they want to risk eating pawpaws or not. (Our recipes only use raw pawpaw fruit, not cooked or dehydrated.)

If you’re a scientist with direct knowledge or expertise in this area, please reach out!

KIGI,

Well, shucks. I’ve wanted I’ve wanted to try pawpaws for years and just bought 2 trees that are out in the backyard waiting to be planted. After watching my grandmother not age gracefully due to brain health, I might just plant one in my yard and gift the other so they don’t pollinate and tempt me. I’ve made it this far without pawpaws. Le sigh.

Sorry, Lindsey. They do taste great. However, like you, we value long-term brain function more than eating a tasty fruit.

More for me,dude. Good grief they are my freaking favorite fruit and produce bliss in my primate brain so they probably are as bad as cocaine and meth,huh? Next your gonna tell me figs kill money brains too. In all seriousness, perhaps not worth the risk of consuming them how many pawpaw lovers consume them every September. I had my first severe acid reflex episode after taste testing hundreds of wild paws around York Pa looking for potential cultivars. Well, I do concur with your decision and it’s probably best to moderate our paw cravings until more long term research is out. Sucks because the Susquehanna I grow is high in that chemical. Perhaps they will hybridize some of the paws protective chemicals out of the delicious morsels.

We love the taste of pawpaws too, Reverend Pawdog. Ha. Too bad pawpaws didn’t consider human brain damage when developing their chemical defense systems millions of years ago.

With respect to pawpaw… Yikes! Is right.

Yes. 🙁

Thank you! I had no idea. They grow wild on my land and I used to eat them as they have a delicious taste. And I also appreciate your explaining the medical terms.

You’re very welcome. We love the taste of pawpaws and will miss eating them every year. Sigh.

Thank you for this information: I live in Illinois, and have wanted to find pawpaw for years (there is even a PawPaw IL, which I wanted to visit)…but now I’m glad I haven’t found any. This is very interesting, and I appreciate the care you are taking in being clear that there isn’t much research, but what there is points to needing more research.

I wonder what happened to the Native Americans who ate a lot of the fruit (including drying and cooking it)?

Thanks, Cecile. It’s impossible to say from today’s vantage point how much pawpaw a particular Native American group ate in a given year, how they prepared them, or what acute or chronic effects may have resulted. As you may know, the average human lifespan wasn’t very long until modern times and nobody was doing epidemiological studies, brain scans, etc. From our personal perspective, there’s enough concerning evidence of health risks to warrant avoiding consumption.